Banished by Bargain:

third Country deportation watch

Monitoring the human cost of

the U.S. government’s forced

third country transfer agreements

The Trump administration has created an opaque web of formal bilateral agreements and behind-the-scenes deals that send asylum seekers and other immigrants – with almost no warning and little chance to raise fears of persecution – to countries with which they have no ties and where many are subject to grave mistreatment including arbitrary detention, torture, or return to danger in the very countries they once fled.

Forced third country agreements also increasingly operate as a coercive tool against people in the United States who are in need of protection. Many agreements are deals reflecting the interests of states that use immigrants and refugees as currency – and deprive them of their rights.

This tracker explains the U.S. third country transfer agreements, the political and financial motives behind them, and the harms they have caused – as well as relevant lawsuits and other efforts to challenge them.

EXPLORE AGREEMENTS BY COUNTRY

Antigua and Barbuda | Belize | Cameroon | Costa Rica

Dominica | Ecuador | El Salvador | Equatorial Guinea

Eswatini | Ghana | Guatemala Honduras | Kosovo

Liberia | Libya | Mexico | Palau | Panama | Paraguay

Poland | Rwanda | South Sudan | St. Kitts and Nevis

Uganda | Uzbekistan

Tracking the Human Cost

Forced third country transfers have separated parents from children, spouses from one another, and cut people off from their communities in the United States. In many cases, they have resulted in enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, and unlawful refoulement (where people are sent to persecution in the country they fled, either directly or via third country).

The toll on individuals and family members is profound: mental anguish, uncertainty, and no safe path to reunification.

What types of agreements and arrangements has the United States made with third countries?

What types of agreements and arrangements has the United States made with third countries?

Arrangements to incarcerate forcibly transferred people in prisons in El Salvador, Eswatini, and South Sudan until eventual onward transfer.

Arrangements for temporary transfer before onward return to home country with Poland and Uzbekistan; in some instances this also included arbitrary detention, with Costa Rica, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, and Panama.

“Asylum cooperative agreements” (ACA) or attempts at “safe third country agreements” (STCA) with Belize, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Paraguay, and Uganda where people transferred purportedly may pursue an asylum claim.

Other types of arrangements that may include detention, onward transfer, and/or remaining in the third country, such as with Guatemala, Mexico, and Rwanda.

*Not enough information is known to categorize arrangements with the following countries: Antigua and Barbuda, Cameroon, Dominica, Liberia, Libya, Kosovo, and St. Kitts and Nevis.

Where have people been sent?

To date, the Trump administration has used these deals to send third country nationals to at least 15 countries (Cameroon, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Eswatini, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Kosovo, Mexico, Panama, Poland, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Uzbekistan). It also attempted to send people to Libya in violation of a court order. The vast majority of third country transfers have been to Mexico.

The administration has also entered into agreements with at least nine other countries, including Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Dominica, Ecuador, Liberia, Palau, Paraguay, St. Kitts and Nevis, and Uganda, where transfers have not yet occurred, as far as is publicly known. In addition, agreements with Sierra Leone and Cape Verde may be finalized or in the process of being finalized.

A separate tool, ICE Flight Monitor, tracks Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) removal flights, including those to third countries, to bring transparency to government operations that are often hidden from public view. This tracker currently does not include removals to the country of origin that involve a layover in a third country—for example, Iranians returned to Tehran via Qatar and Kuwait, Venezuelans returned to Caracas via Honduras, or Russians returned to Moscow via Egypt. It also does not track ad hoc forced third country transfers carried out on commercial flights.

Why is the Trump administration doing this?

The administration’s policy punishes immigrants and asylum seekers and deprives them of their rights under U.S. law. The administration is disappearing people to unknown locations before family members and lawyers can help them, sending them to face arbitrary detention, torture, chain refoulement, and other harms. The mistreatment in the third country is inflicted not for any crime committed there or in the United States, but because they were immigrants in the United States subjected to a forced transfer arrangement.

The administration is wielding the threat of forced transfers to terrify immigrant communities and force people to leave the United States, including by publicly warning “If you do not leave, we will hunt you down, arrest you, and you could end up in this El Salvadorian prison.” In some cases, the administration directly threatens individual detained immigrants with transfer to a third country in order to coerce them to relinquish their rights and abandon their immigration cases. In some cases, the U.S. government seems motivated to not only punish immigrants and terrify others, but perhaps also to pressure other governments into accepting the return of their own nationals.

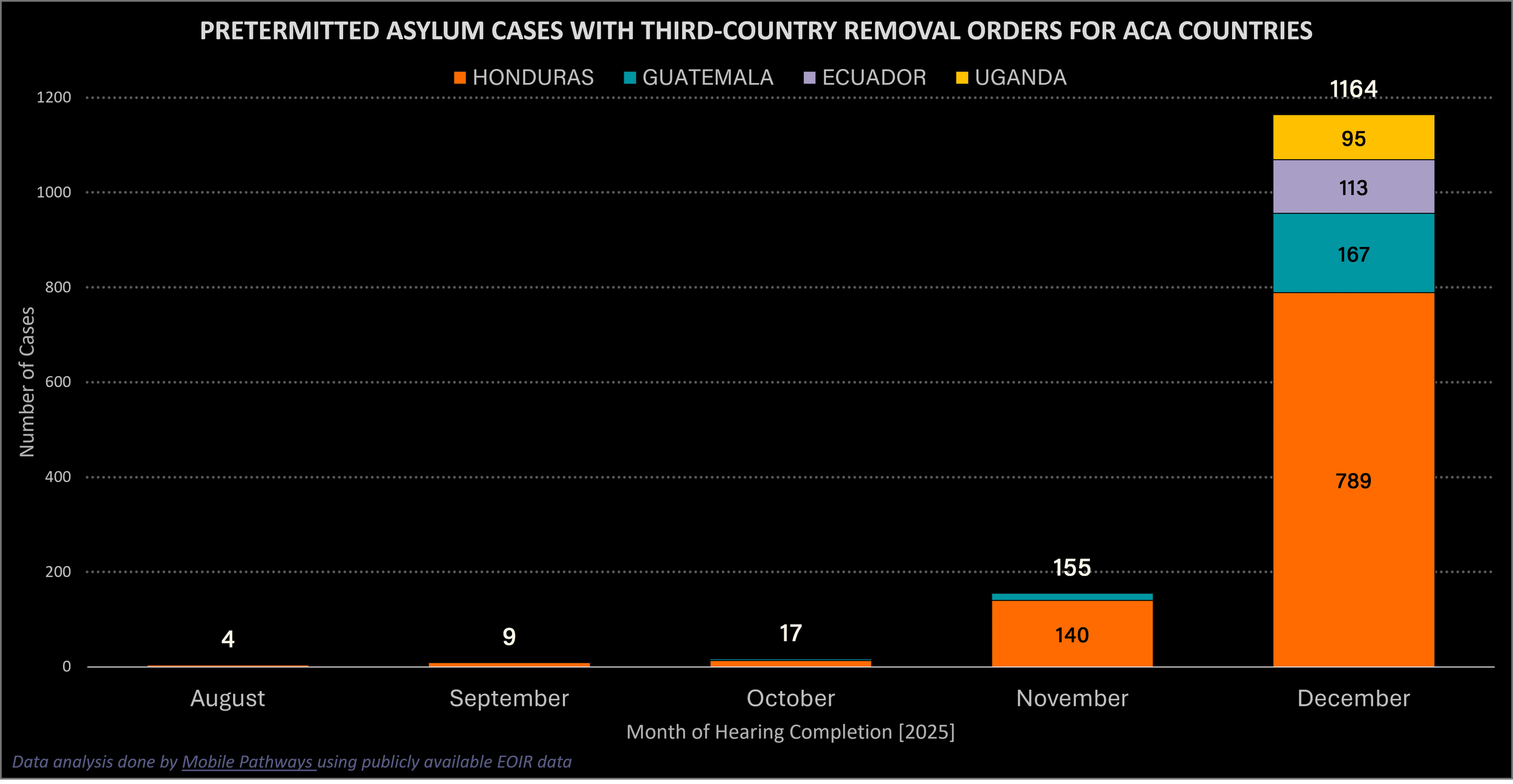

The administration has also pretermitted—refused to consider on the merits—more than 1,000 asylum applications and subsequently designated individuals for removal to third countries with which the United States has signed asylum cooperative agreements. After pretermitting a person’s case, the government may detain people for prolonged periods. As of January 2026, the organization Mobile Pathways has used publicly available Executive Office of Immigration Review data to track almost 1,350 pretermissions of individual asylum cases with an Asylum Cooperative Agreement Country (Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, or Uganda) listed as the first country of removal for non-nationals of those countries. Third Country Deportation Watch has tracked only about 30 total transfers under any of the Asylum Cooperative Agreements (all to Honduras). Thus pretermissions seem aimed to force people in need of protection to abandon their claims, to deter others from seeking protection in the United States, and to put vulnerable people at risk of harm in U.S. detention or through removal.

Who is being sent to third countries through these deals?

The Trump administration has used these deals to banish to third countries men, women, children, families, and pregnant people, as well as individuals with medical or psychological vulnerabilities, and those with recognized legal protection claims. People who have been forcibly transferred from the United States under these arrangements have come from a wide range of countries across the globe. This tracker’s country sections specify the nationalities and number of people sent to each third country.

The administration has forcibly transferred asylum seekers and other migrants at various stages of their immigration case, including:

people arriving in the United States to seek asylum who are expelled without consideration of their claim

people in the midst of their immigration court case who have not received a full hearing on their asylum claim or a decision from a judge

people approved for refugee resettlement by U.S. refugee officers

people already granted protection under the Convention Against Torture (CAT) or withholding of removal because of likely persecution in their home country

people with final orders of removal for whom removal to the third country was never raised by the government

Why would other countries agree?

Through forced third country transfer agreements, the Trump administration has warped U.S. international relations in service of its deportation agenda. In many cases, the reasons countries have agreed to receive third country nationals remain murky, often bound up in pressure and incentives from the Trump administration, as well as broader bilateral geopolitical and financial interests. At the time that many of these agreements were signed and implemented, the Trump administration imposed or threatened third countries with visa bans, tariffs, and other trade barriers as detailed in the country sections. The Trump administration also has provided funding to some of the third countries, including for migration and border enforcement, defense, and condoned corruption, repression, and violations of human rights by governments in third countries. Some deals seem to be tied to U.S. support for public health or other aid, albeit more restricted and limited than the U.S. provided in the past given massive U.S. cuts in humanitarian aid. The agreements may continue to push other countries to violate their human rights commitments, further undermining the rule of law globally.

Is it legal?

The administration has used a range of tactics to attempt to justify these transfers, some in unprecedented ways. To justify some of the transfers, the Trump administration has unlawfully invoked Constitutional authority to respond to an “invasion” and a centuries-old wartime law (the Alien Enemies Act), casting people seeking safety as a threat. It has also intentionally evaded other statutory provisions such as those governing safe third country agreements, countries to which people with final orders of removal may be removed, and a provision regarding “suspension of entry” for certain noncitizens that was enacted long before codification of the Refugee Convention and its Protocol.

Legal services organizations and immigrants have challenged the forced transfers and third country arrangements in U.S. courts, which have already held them to be unlawful in some cases. The Trump administration has continued to forcibly transfer people to harms in third countries, at times in direct violation of court orders.

Lawyers and members of civil society in third countries have brought challenges in their courts and international and regional bodies regarding their governments’ treatment—including detention, refoulement, and other human rights violations—of those transferred by the United States to their counties. Politicians in third countries have demanded more transparency regarding the agreements and other governments have at times refused to sign third country agreements and denied requests for transfers from the Trump administration.

Members of the U.S. Congress and international bodies have condemned the unlawfulness of forced transfers and the lack of transparency around the agreements.

What are Forced third country transfers?

We are using this term to describe the deportation or expulsion of individuals from the United States to third countries where they are not citizens and to which they are forcibly sent, often exposing them to harm or the risk of chain refoulement. These transfers occur through various bilateral agreements and arrangements between the United States and other governments.

What are Enforced Disappearances?

The arrest, detention, abduction, or other deprivation of a person’s liberty by state agents—or by others with the state’s approval, support, or acquiescence—followed by a refusal to acknowledge the detention or by hiding the person’s fate or whereabouts. This places the person outside the protection of the law.

What is arbitrary detention?

Arbitrary detention is the deprivation of liberty that lacks a legal basis, such as conviction for a crime, or, even when tethered to a cause and authorized by law, is unreasonable or disproportionate and carried out without due process. Detention is considered arbitrary when individuals are detained without relation to their own actions, not promptly informed of the reasons for their detention, are denied access to judicial review or the ability to challenge its lawfulness, are held for prolonged or indefinite periods, or are detained in a discriminatory manner. Even where domestic law permits detention, it may still be arbitrary if it is unnecessary or lacks justification or adequate procedural safeguards.